Natalie Davis

The Man with the 'Face of Christ'

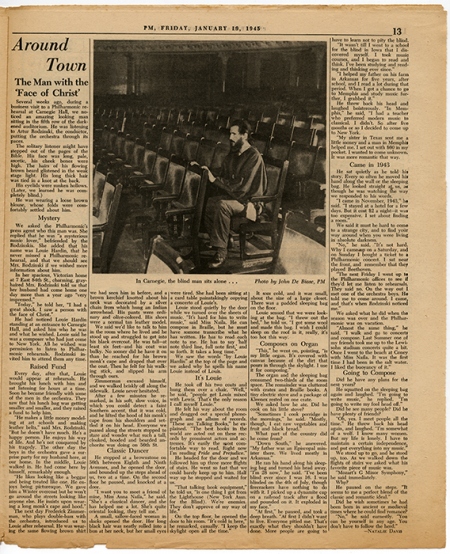

Several weeks ago, during a business visit to a Philharmonic rehearsal at Carnegie hall, we noticed an amazing looking man sitting in the 5. row of the darkened auditorium. He was listening to Artur Rodzinski, the conductor, putting the orchestra through the paces.

Several weeks ago, during a business visit to a Philharmonic rehearsal at Carnegie hall, we noticed an amazing looking man sitting in the 5. row of the darkened auditorium. He was listening to Artur Rodzinski, the conductor, putting the orchestra through the paces.The solitary listener might have stepped out of the pages of the Bible. His face was long, pale, ascetic, his cheek bones were high. The hairs of his flowing brown beard glistened in the weak stage light. His long thick hair was tied in a knot at the back. His eyelids were sunken hollows. (Later, we learned he was completely blind.) He was wearing a loose brown blouse, whose folds were comfortably settled about him.

Mystery

We asked the Philharmonic's press agent who this man was. She replied that he was "a mysterious music lover," befriended by the Rodzinskis. She added that his name was Louie Hardin, that he never missed a Philharmonic rehearsal, and that we should see Mrs. Rodzinski if we wished more information about him.

In her spacious, Victorian home at 7 East 84th St., charming, grayhaired Mrs. Rodzinski told us that her husband had come home one day more than a year ago "very impressed". "Today," he told her, "I had a great shock. I saw a person with the face of Christ."

He had noticed Louie Hardin standing at an entrance to Carnegie Hall, and asked him Who he was and what he wished. Louie said he was a composer who had just come to New York. All he wished was permission to listen to Philharmonic rehearsals. Rodzinski invited him to attend them any time.

Raised Fund

Every day, after that, Louie would appear at rehearsals. He brought his lunch with him and sat listening for hours at a time. Soon he became friendly with some of the men in the orchestra. They saw that his lunch bag was getting smaller, and they raised a fund to help him.

"He makes a little money modeling at art schools and making leather belts," said Mrs. Rodzinski. "But he doesn't have much. He's a happy person. He enjoys his way of life. And he is not conquered by his tragedy. The other day the boys of the orchestra gave a surprise party for my husband here, at our home. In the middle, Louie walked in. He had come here by himself, remarkably enough".

"He likes looking like a beggar and being treated like one. He enjoys being picturesque. We gave him a winter overcoat but he won't go around the streets looking like anyone else. He insists upon wearing a long monk's cape and hood."

The next day Frederick Zimmermann, who plays double-bass with the orchestra, introduced us to Louie after rehearsal. He was wearing the same flowing brown shirt we had seen him in before, and a brown kerchief knotted about his neck was decorated by a silver chain from which hung an Indian arrowhead. His pants were ordinary and olive-colored. His shoes were a normal tan leather model.

We said we'd like to talk to him in the room where he lived and he stood up and struggled to get into his black overcoat. He was tall - at least six feet - and his coat was bulky. No sooner did he have it on than he reached for his brown monk's cape and draped that over the coat. Then he felt for his walking stick, and slipped his arm through ours. Zimmermann excused himself, and we walked briskly off along the sidewalk. Louie never hesitated.

After a few minutes he remarked in his soft, slow voice, in which you could detect a faint southern accent, that it was cold, and he lifted the hood of his monk's cape from his shoulders and settled it on his head. Everyone we passed along the street stopped to stare and wonder what such a tall, cloaked, hooded and bearded anchorite was doing on 56. St.

Classic Dancer

He stopped at a brownstone on 56th between Eighth and Ninth Avenues, and he opened the door and bounded up the steps ahead of us, two at a time. On the second floor he paused, and knocked at a door.

"I want you to meet a friend of mine, Miss Anna Naila," he said. "She's a classical dancer, and she has helped me a lot. She's quite oriental looking, they tell me."

A small, sallow-faced woman in slacks opened the door. Her long black hair was neatly rolled into a bun at her neck, but her small eyes were tired. She had been sitting at a card table painstakingly copying a concerto of Louie's.

Louie stood quietly by the door while we turned over the sheets of music. "It's hard for him to write music," said Miss Naila. He can compose in Braille, but he must have someone transcribe what he has written. He has to read each note to me. He has to say 'half note third line, full note first,' and so forth. It takes a long time."

We saw the words "by Louie Hardin" at the top of the page and we asked why he spells his name Louie instead of Louis.

It's Louie

He took off his two coats and hung them over a chair. "Well," he said, "people get Louis mixed with Lewis. That's the only reason I call myself Louie."

He felt his way about the room and dragged out a special phonograph and an album of records. "These are Talking Books," he explained. "The best books in the world are acted out on these records by prominent actors and actresses. It's easy and a comfortable way to read. Right now I am reading 'Pride and Prejudice'."

He headed for the door and we followed him up three more lights of stairs. He went so fast that we could barely keep up to him. Half way up he stopped and waited for us.

"That talking book equipment," he told us "is one thing I got from the Light-house (New York Assn. for the Blind). We're enemies. They don't approve of my way of life."

On the top floor, he opened the door to his room. "It's cold in here," he remarked, casually. "I keep the skylight open all the time."

It was cold, and it was small, about the size of a large closet. There was a padded sleeping bag on the floor.

Louie sensed that we were looking at the bag. "I threw out the bed," he told us. "I got some wool and made this bag. I wish I could sleep on some roof in it, really, it's good to sleep that way."

Composes on Organ

"This," he went on, pointing, "is my little organ. It's covered with canvas because of the dirt that pours in through the skylight. I use it for composing."

The Organ and the sleeping bag consumed two-third of the room space. The remainder was cluttered with crates and Braille books. A tiny electric stove and a package of Kleenex rested on one crate.

We asked how he ate. Did he cook on his little stove?

"Sometimes I cook porridge in the mornings," he said. "Mostly, though, I eat raw vegetables and fruit and black bread."

What part of the country did he come from? "I was born in Kansas and lived in many different states," he answered. "My father was an Episcopal minister."

He ran his hand along his sleeping bag and turned his head away. "I'm 28 now," he said, "I've been blind ever since I was 16. I was blinded on the 4th of July, though firecrackers had nothing to do with it. I picked up a dynamite cap on a railroad track after a flood and pounded on it. It exploded in my face."

"At first," he paused and took a deep breath, "at first I didn't want to live. Everyone pitied me. That's exactly what they shouldn't have done. More people are going to have to learn not to pity the blind. "It wasn't till I went to school for the Blind in Iowa that I discovered myself. I took music courses, and I began to read and think. I've been studying and reading and thinking ever since."

"I helped my father on his farm in Arkansas for five years, after school, and I read a lot during that period. When I got a chance to go to Memphis and study music further, I grabbed it."

He through back his head and laughed boisterously. "In Memphis," he said, "I had a teacher who preferred modern music to classical. I didn't. So after five months or so I decided to come up to New York."

"My sister in Texas sent me a little money and a man in Memphis helped me. I set out with 60 dollars in my pocket. I wanted to come unknown. It was more romantic that way."

Came in 1943

He sat quietly as he told his story. Every so often he moved his hand along the wall or the sleeping bag, he looked straight at us, as though he was watching the way we responded to his words.

"I came in November, 1943," he said, "I stayed at a hotel for a few days. But it cost 2 dollars a night - it was too expensive. I set about finding a room." We said it must be hard to come to a strange city, and to find your way around when you were living in absolute darkness. "No," he said. "It is not hard. Why I came up on a Saturday, and on Sunday I bought a ticket to a Philharmonic concert. I sat near the front, and remember that they played Beethoven."

"The next Friday I went up to the Philharmonic offices to see if they'd let me listen to rehearsals. They said no. On the way out I met one of the orchestra boys. He told me to come around. I came, and that's when Rodzinski noticed me."

We asked what he did when the season was over and the Philharnionic was on vacation. "Almost the same thing," he said, "I walk and go to concerts and compose. Last summer one of my friends took me up to the Lewisohn Stadium concerts quite a bit. Once I went to the beach at Coney with Miss Naila. It was the first time I had been in the salt water. I liked the buoancy of it."

Going to Compose

Did he have many plans for the next years?

He squatted on the sleeping bag again and laughed. "I am going to write music," he replied. "I'm gong to write my fool head off." Did he see many people? Did he have plenty of friends?

"Oh, yes, I meet people all the time." He threw back his head again and laughed. "I'm somewhat of a wolf. I know many women. But my life is lonely."

We stood up to go, and he stood up, too. As we walked down the flight of staurs we asked what his favourite piece of music was.

"Mozart's G minor Symphony," he said immediately.

Why?

He paused on the steps. "It seems to me a perfect blend of the classic and romantic ideal."

Did he wish sometimes he had been born in ancient or medieval times where he could find romance?

"No," he said earnestly. "You can be yourself in any age. You don't have to follow the herd."